View All Honorees

View All Honorees

Columbia City of Women Honoree

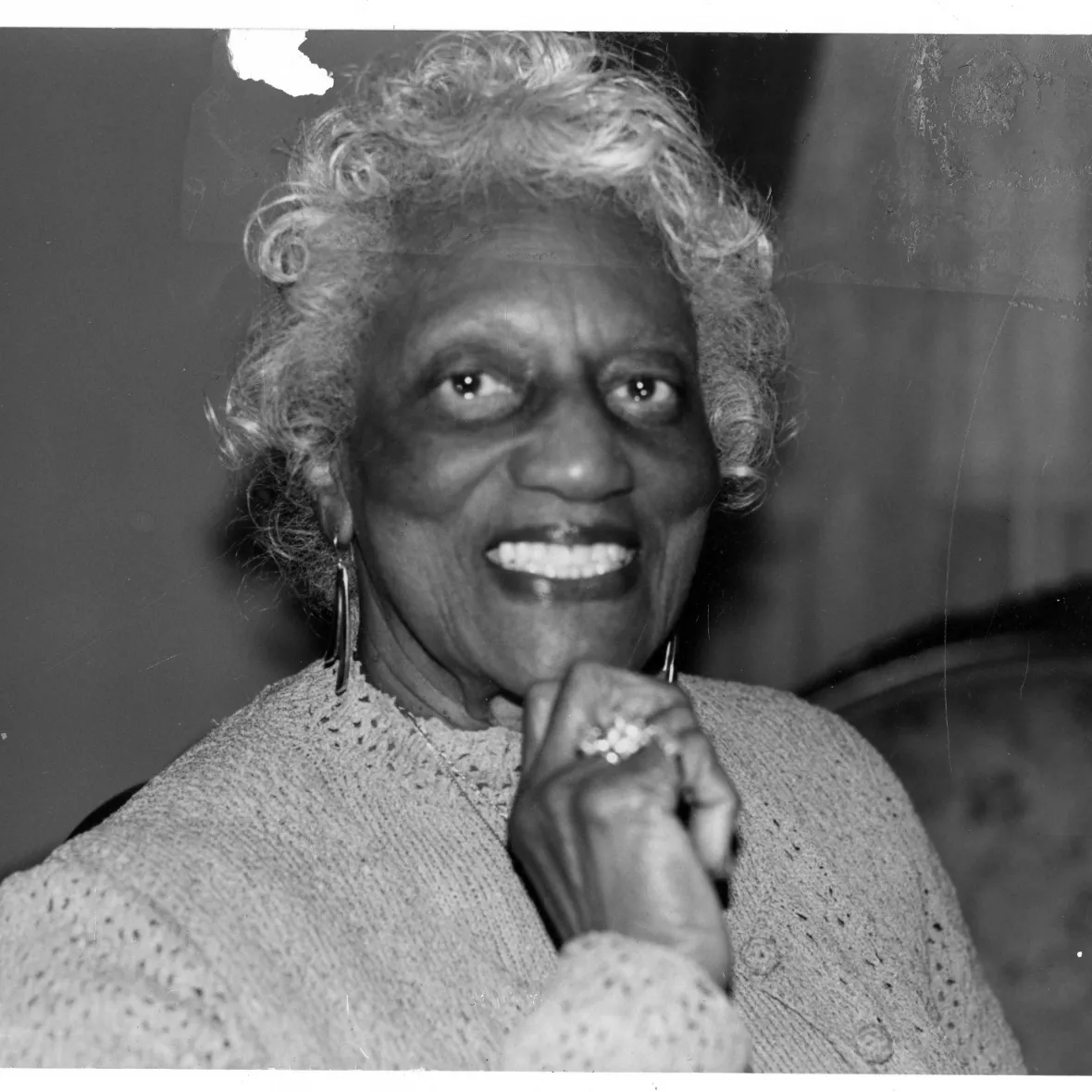

Donella Brown Wilson

Image courtesy Minnie Wilson Bivens

On August 10, 1948, Donella Brown Wilson took her place in line among hundreds of Black citizens living in the Ward 9 voting precinct. They joined an estimated 30,000 black voters, newly enfranchised by the recent court rulings Elmore v. Rice and Brown v. Baskin, in casting ballots in South Carolina’s Democratic Primary “for the first time in history.” Wilson, by then a 39-year-old mother, was one of many who voted for the first time that day. She never missed another election, voting in local, state, and national contests for the next 70 years.

Donella Roberta Brown was born on May 24, 1909, on the Peterkin Plantation in Fort Motte, Calhoun County, where her grandparents and great-grandparents were once enslaved, and where her parents, Henry and Minnie Bryant Brown, continued to work as sharecroppers. An only child, Brown lived with her parents and maternal grandmother, Mary Weeks Bryant, in a three-room house with no water or electricity. She did not have access to formal schooling, and instead learned to “read” by studying the pages of a Sears & Roebuck catalog and by listening to her grandmother read from the Bible. Her grandmother, who was a domestic worker and head gardener at Lang Syne, also served as a cultural liaison between the plantation’s black tenants and its white owner, Julia Peterkin. Peterkin, who once called Mary Weeks Bryant her “best black friend,” used the broad strokes of her life as inspiration for the title character in Scarlet Sister Mary, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1929. Life on the plantation was not dissimilar to the time before slavery ended; each morning, Brown’s parents, relatives, and neighbors would gather in “the yard” to receive their labor assignment. Brown recalled “boiling clothes and making soap and canning in jars” as a young child.

Henry Brown died in the early 1910s, and Minnie and Donella Brown moved to Charleston and then Columbia in 1914. Minnie Brown married John Logan and had another daughter, Mary. The family lived near Union Station in the 700 block of Gates (Park) Street in the Ward One neighborhood. Seven days a week, Minnie Brown Logan walked across town to the 2400 block of Devine Street, where she cooked and cleaned for the Quattlebaum family for $5 a week. In 1928, they purchased a lot at 2002 Senate Street and constructed a two-room dwelling. Mary Weeks Bryant joined her daughter and granddaughters after the death of John Logan later that year.

Donella Brown recalled joining the NAACP in the eighth grade, when dues were 25 cents. Although the organization struggled to retain members in the early 1920s, it experienced sustained growth beginning in 1926, and this is likely when she joined. That year, black Columbians were driven to organize following the lynching of the Lowman relatives, one of whom was a young woman, and another of whom was a teenage boy. Decades later, Brown recalled one instance that was typical of the injustices her family experienced in the Jim Crow period. Her ten-year-old cousin, who was staying with the Browns and working as a shoe shiner in Five Points to earn money for his family at the Peterkin Plantation, came home crying. One customer that day had chosen not to pay him, and then kicked him when he protested. A policeman who witnessed the incident did nothing.

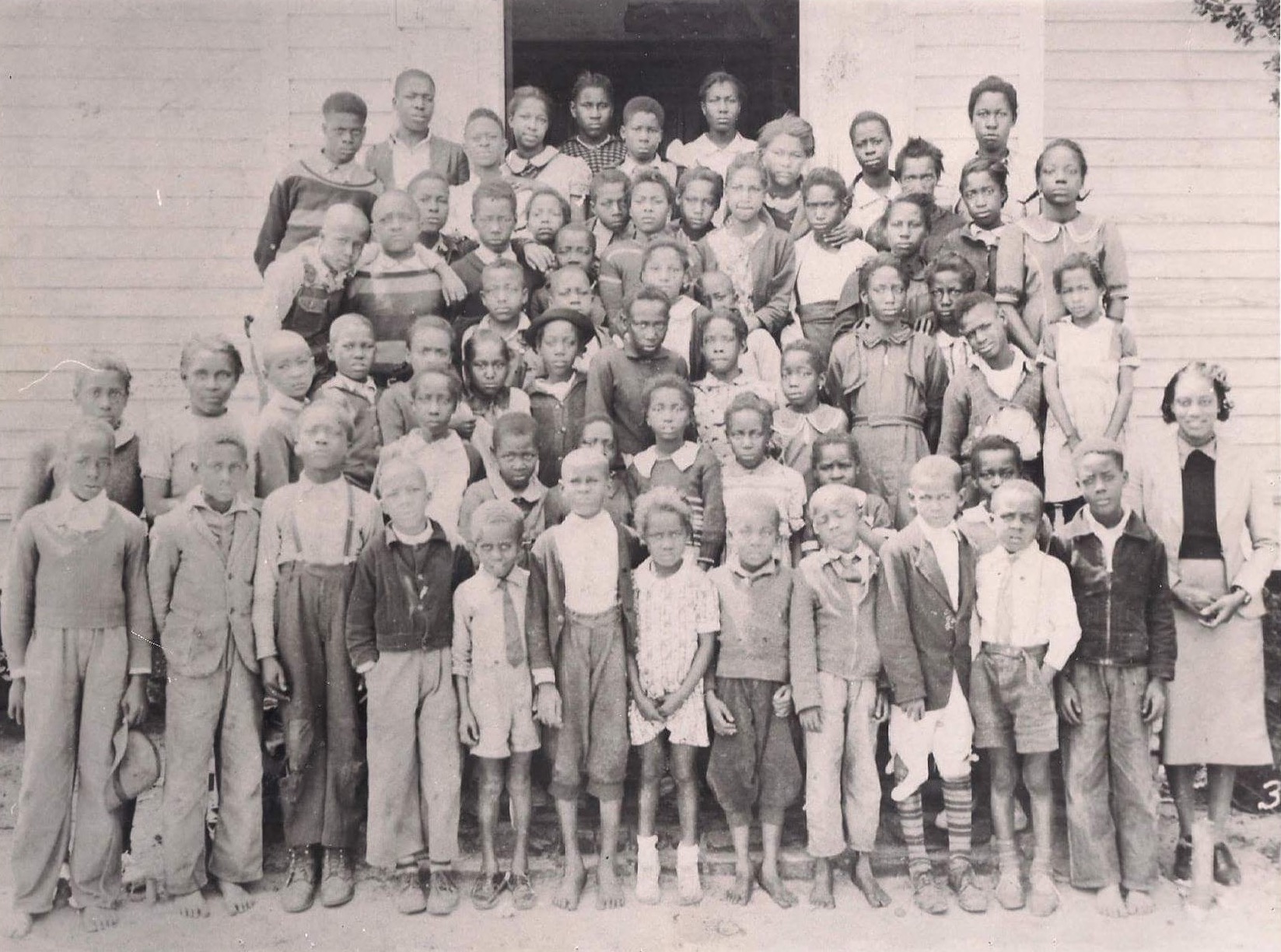

Minnie Brown, who obtained only a third-grade education, pushed for both of her daughters to finish school and find careers. Both Donella and Mary attended Booker T. Washington in grade school, and they even caught rides with Modjeska Monteith on the way to school while Monteith taught there in the 1920s. Both later transferred to Allen University, where they attended the high school program.

Donella Brown married her high school sweetheart, John R. Wilson, in 1931. Two years later, she graduated from Allen University’s teacher training program. Married women could not teach in Columbia’s public schools, so she took positions in rural counties, including Orangeburg and Lexington counties. Her husband also taught in Lexington and later served as pastor of Union Baptist Church. In 1937, the Wilsons purchased 1214 Heidt Street in the Waverly neighborhood where they raised four children.

In the late 1940s, after the NAACP successfully sued for equal pay for black teachers, the Wilsons and other teachers at the high school in Lexington requested supplemental pay and sick leave on par with their white counterparts in other schools. The superintendent gathered the teachers together to ask who had made the request; only John Wilson stood up. The couple’s contracts were not renewed. Donella Wilson returned to work at Roberts High school in Holly Hill, Orangeburg, County. She stayed at a boarding house during the week for nearly 20 school years, before retiring in 1971.

Several photographs of the landmark 1948 election survive. They were taken by George Elmore, the plaintiff in the 1946 suit Elmore v. Rice, which struck down the all-white Democratic Party. Wilson, umbrella in hand, appears in one. The Wilsons remained active in the NAACP during the 1940s and 1950s, even as White Citizens Council members, who were especially active in Orangeburg County, threatened all members or sympathizers with unemployment and economic ruin. As an act of defiance, Wilson would carry her membership card in her pocketbook, but she chose not to share her affiliation with her employer. Elmore, as the face of the primary lawsuit, ultimately bore the full brunt of white Columbians’ anger. Donella Wilson, who lived near his Waverly Five-and-Dime store, later recalled that “after he got the vote, [vendors] wouldn’t sell him anything. He did all he could to make it. He just deteriorated.”

After she reached 100, Wilson began sharing her life story, and in doing so illuminating the sacrifices her generation made to bring civil rights to South Carolinians. As she once told historian Bobby Donaldson, “every time we voted, we kept losing. Every time, and yet we kept voting.” She died in 2017, having lived to vote for the first black president.

SHE DID, so that we can ALL exercise our right to vote.

Want to learn more about Donella Brown Wilson? Connect with a historian at Historic Columbia.

Interested in advancing the health, economic well-being, and rights of South Carolina's women, girls, and their families? Check out what's going on at WREN.

On August 10, 1948, a 39-year-old Donella Brown Wilson took her place among hundreds of African Americans waiting to vote at this service station, built in 1936. Wilson and her fellow voters finally won this right after the NAACP challenged the legality of South Carolina’s all-white Democratic Primary. The station was demolished in the early 1950s.